Transform Your Fitness Mindset. How to Finally Make Time for Exercise and Make it Stick.

Anyone can tell you that exercise is good for you. And lots of people will—including me. But I’m not going to do that today, and here’s why: hotel room attendants.

In a 2007 study, Stanford University researchers educated 84 hotel room attendants on the benefits of exercise and shared the Center of Disease Control’s (CDC’s) guidelines for daily activity [1]. Then the scientists took half the attendants aside and gave them some additional information.

These participants were told that changing linens, vacuuming, and cleaning toilets all counted as exercise, and because they were servicing—on average—15 rooms a day, they were actually exceeding the CDC’s recommendations.

What happened? Neither group changed their daily activity levels. But, surprisingly, after 4 weeks, the “informed group” had lost weight, body fat, and inches off their waist and significantly lowered their blood pressure. The “uniformed group” didn’t.

Which goes to show: How you think about exercise—and yourself—can have a profound effect on your health outcomes. What’s more, just telling people how great exercise is probably isn’t that helpful.

That’s why I’m not going to try to convince you how important exercise is. Instead, I’m going to give you powerful strategies—from the insanely cool field of exercise psychology—that’ll help you eliminate what’s really in the way: common barriers and limiting mindsets such as “I don’t have time,” “I don’t have motivation,” and “I don’t like exercise.” It could be just what you need to transform your fitness forever.

Obstacle #1: “I don’t have time to exercise.”

Lots of people say they’re “too busy to work out.” Maybe even you. But is that really true—or just what you believe? There’s a way to find out, and it’s based on a novel experiment from scientists at Leeds Metropolitan University [2].

In the study, researchers had people exercise during work hours on some days, and do no activity on others. At the end of each day, participants rated their work productivity on a scale of 1 to 7 (1 = worst; 7 = best).

The result: People were 15 percent more productive on the days they exercised than on days they didn’t. So, in an 8-hour workday, that level of increased productivity means you could fit in an hour of exercise—plus 12 minutes to clean up—and not see a dropoff in your overall performance.

Don’t buy it? Put it to the test and track your own work productivity on the days you do and don’t exercise. You might be pleasantly surprised.

Obstacle #2: “I don’t feel motivated to exercise.”

I’m about to tell you the secret to motivation. But fair warning: It can be a bit of a mind-bending idea. That’s because it’s the opposite of what everyone thinks. Well, everyone except psychologists.

Here it is: Taking action is what leads to motivation—not the other way around. This concept is based on something called “self-perception theory,” which was introduced in the 1970s by Daryl Bem, PhD, a famed psychologist who’s now a professor emeritus at Cornell University.

Self-perception theory suggests that people develop their attitudes and emotions—key drivers of motivation—by observing their own behaviors. So by taking action, even when you don’t feel motivated, your brain infers that you are indeed motivated.

As a result, just doing something can be a powerful momentum builder. For example, imagine you’re struggling to start a workout routine. Instead of waiting to feel motivated, you take a simple action—like putting on your workout clothes and going for a 5-minute walk. Anything that lets you check the “I exercised” box counts. The next day, you do it again. A few days later, you add one more minute to your walk, or toss in a set of pushups and bodyweight squats.

Over time, these consistent actions—no matter how small—accumulate and create a positive feedback loop. As your brain observes this pattern of behavior, it starts to shift your attitudes and emotions, gradually building your motivation to exercise more regularly. That’s when the real magic starts to happen.

Obstacle #3: “I don’t like exercise.”

Admittedly, this can be a hard one to get around. The standard advice is to “find an activity you enjoy.” While I endorse this sentiment 100 percent, it’s often not that easy to do. For instance, maybe there’s not an obvious choice, or the one activity you’d love to do regularly is wildly impractical (you’re obsessed with horseback riding but live in downtown Detroit).

So here’s another option: temptation bundling.

Temptation bundling is a concept developed by Katy Milkman, PhD, and a team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. It involves bundling a “should” (exercise) with a “want” or “temptation” (something else you really enjoy).

In 2014, the researchers conducted a study to see if it’d work. They gave one group of gym goers a “tempting” audiobook of their choosing—The Hunger Games was most popular—but with an important caveat: The participants could only listen to it while exercising on a treadmill or other aerobic machine [3]. Turns out, these folks worked out 51 percent more frequently than gym members who weren’t given an audiobook.

“This pairing makes ‘should’ activities more enticing and therefore more likely to be readily executed; it also makes ‘want’ activities less wasteful and guilt-inducing.” [4]

So what’s your Hunger Games? What’s an audiobook, podcast, or TV show you love? Save it for your exercise session, and see if it makes working out feel more enticing.

Obstacle #4: “I start out with good intentions, but I never stick with it.”

If you find yourself struggling with this obstacle, ask yourself why. Applying Occam’s Razor—the idea that the simplest explanation is often the right one—might reveal that you’re choosing to do something that’s too hard for you.

For instance, if you go from not exercising at all to trying to exercise for an hour a day, it’s likely going to be too much. It completely changes your daily routine and can feel overwhelming. When something is too hard, it’s natural to want to quit. But there’s another option: Make it easier.

Start by deciding on an amount of exercise you feel you can do. Before committing, ask yourself, “On a scale of 1-10, with 1 being ‘it sounds impossible’ and 10 being ‘I can do this in my sleep,’ how likely am I to follow through?” If your answer isn’t a 9 or 10, make it easier. Repeat until you get there.

Obstacle #5: “When it comes to exercise, I’m an all-or-nothing person.”

Ever plan on doing a 30-minute workout, but realize you only have 26 minutes, so you skip the whole thing? You might defiantly say, “If I can’t do my full workout, it’s not worth doing at all!”

This type of all-or-nothing thinking is very common. So common, in fact, there’s a name for it: It’s a “cognitive distortion,” a term popularized by David Burns, MD, a renowned psychiatrist, to describe irrational thought patterns that skew your perceptions, hinder your progress, and mostly make you miserable.

To overcome this, practice thinking on a continuum. If you can’t do 30 minutes, can you do 26? Or 20? Or 10? Even a shorter workout is better than none and helps build the habit of consistency and keep your momentum going. (See Obstacle #2.) Each time you make a choice along the continuum—instead of sticking strictly to a binary option—you’re demonstrating what psychologists call “cognitive flexibility.” And who wouldn’t want that?

References

-

Crum AJ, Langer EJ. Mind-set matters: exercise and the placebo effect. Psychol Sci. 2007 Feb;18(2):165–71.

- Coulson JC, McKenna J, Field M. Exercising at work and self‐reported work performance. Int J Workplace Health Manage. 2008 Jan 1;1(3):176–97.

- Milkman KL, Minson JA, Volpp KGM. Holding the Hunger Games Hostage at the Gym: An Evaluation of Temptation Bundling. Manage Sci. 2014 Feb;60(2):283–99.

- Kirgios EL, Mandel GH, Park Y, Milkman KL, Gromet DM, Kay JS, et al. Teaching temptation bundling to boost exercise: A field experiment. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020 Nov 1;161:20–35.

Related Longevity Articles

-

-

-

-

8 min read

8 min readFresh Starts and Fast Results: Your 10-Day Plan for the New Year

Diet & Nutrition Longevity -

9 min read

9 min readAmerica’s New Dietary Guidelines Get the Big Picture Right—and That’s a Big Deal

Diet & Nutrition Longevity -

-

-

Sports Nutrition/Fitness Support

-

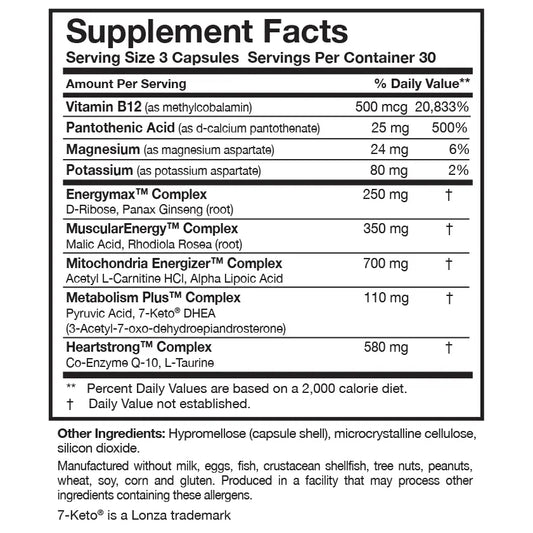

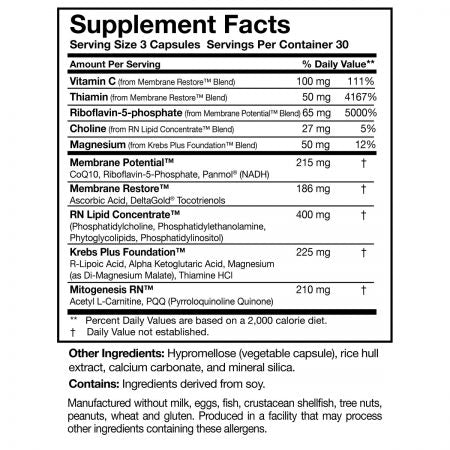

Energize Plus Pure Packs

Regular price $75.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

B-Complex Plus

Regular price $42.00 / 120 CapsulesRegular priceUnit price / per -

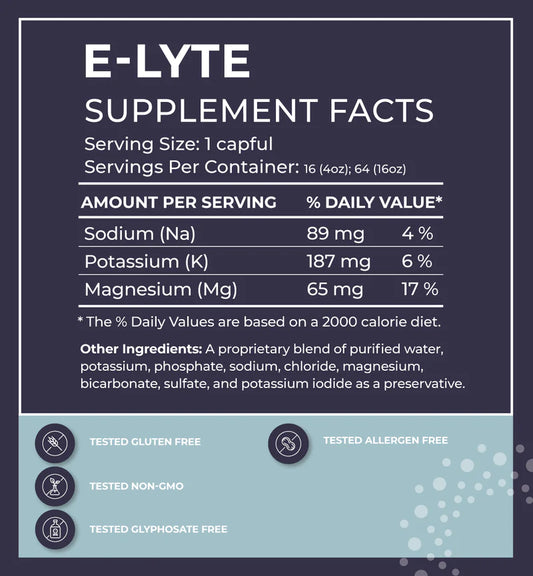

E-lyte Balanced Electrolyte Concentrate 16 oz.

Regular price $30.99 / 16oz LiquidRegular priceUnit price / per -

Bioactive Collagen Complex Daily Foundational Support

Regular price $59.00 / 13.9 oz PowderRegular priceUnit price / per -

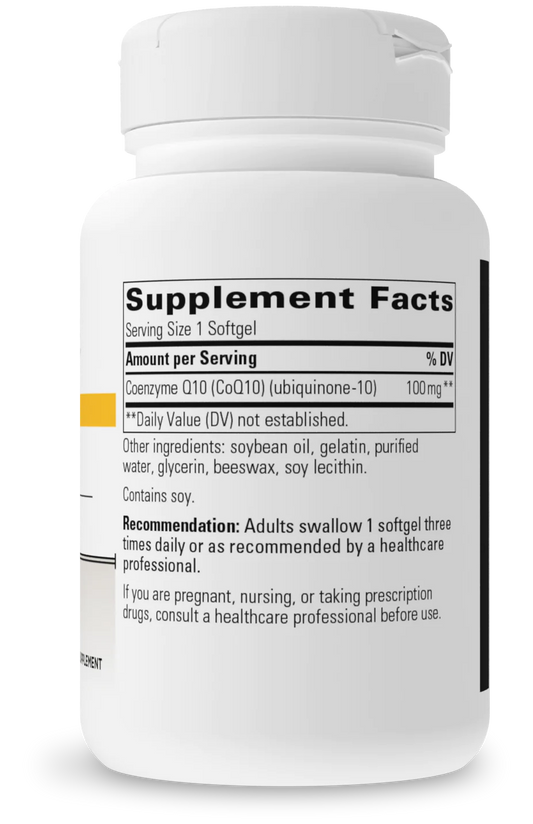

CoQ10 100mg

Regular price $43.00 / 60 SoftgelsRegular priceUnit price / per -

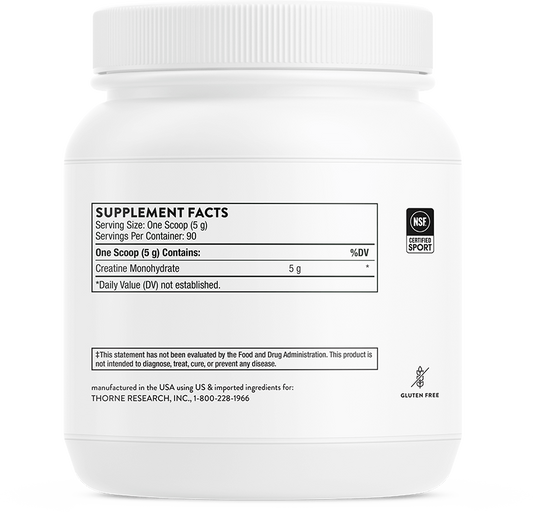

Creatine

Regular price $44.00 / 90 ScoopsRegular priceUnit price / per -

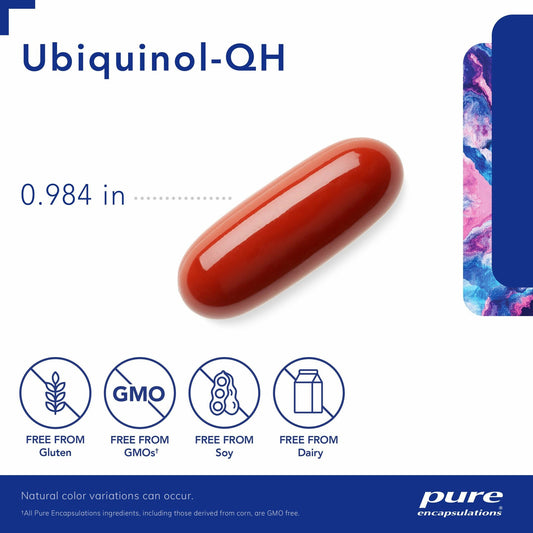

CoQ10: Ubiquinol QH: 100 mg

Regular price $99.00 / 60 SoftgelsRegular priceUnit price / per -

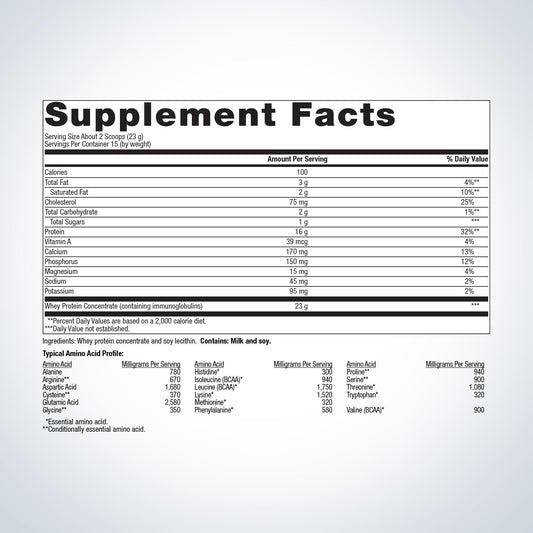

BioPure Protein

Regular price $51.25 / 15 ServingsRegular priceUnit price / per -

Wellness Essentials® Active Daily Packs

Regular price $90.00 / 30 PacketsRegular priceUnit price / per -

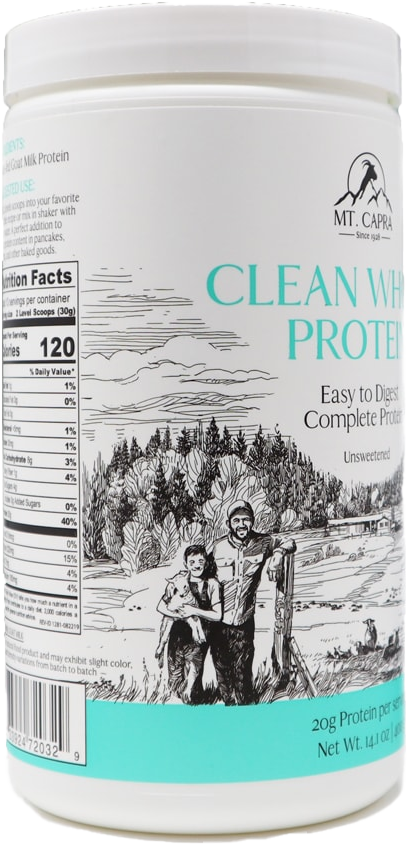

MT. Capra Grass-Fed Goat Milk Protein Powder

Regular price $39.00 / 26 ScoopsRegular priceUnit price / per -

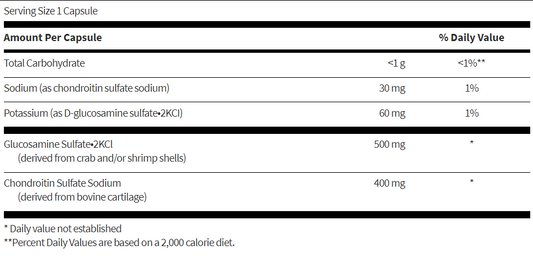

Glucosamine/Chondroitin

Regular price $40.99 / 90 CapsulesRegular priceUnit price / per

Login

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.