Dr. Hyman's Haiti Journal - Day 5: Shaken Again

PLEASE NOTE: THIS blog is a reprint of an article that appeared on Huffington Post.

Days 4 & 5

I slept through the aftershock this morning, a small 6.1 earthquake that has had no real impact because everything that could be destroyed was already destroyed. But the aftershocks that will ripple through the lives of the Haitian people will last for decades. They will for Mitch, who I met the first morning at the hospital grounds. He was laying in the back alley, unattended for four days except for a small bandage around his knee. He called out softly in English for me to stop, to help him. He had not eaten nor drank water since the quake and was still smiling at me. He lost his entire family — a wife and three children — and home. He was alone with no one to care for him, unlike some of the other patients who were tended to by their less-wounded family members, bringing what food and water they could.

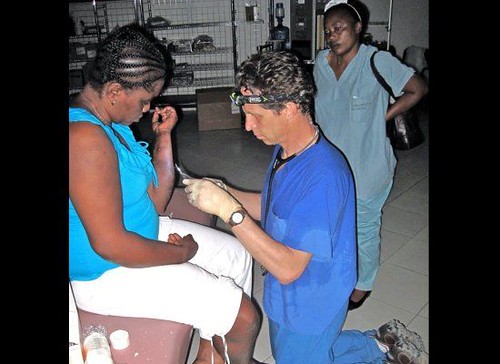

I kneeled down and opened his dressing. A quart of foul pus spilled out from his knee, which was shattered and crushed. Pier, my wife, is an orthopedic surgeon. She came over and said he needed to be the next surgery case.

George Boutin, my father-in-law, didn’t have the heart to remove his mangled fingers and hand. He reconstructed them so the musician could, perhaps, play music again. Maybe. Perhaps. Hopefully one day.

But the volume of trauma and mangled limbs is staggering.

I saw him a few days later, finally inside the make-shift pre-op area — still with almost no water, food, antibiotics nor pain medication. He smiled again when he saw me and grabbed my hand.

I brought General Keen from U.S. Southern Command, who is leading the military relief and support effort for the Haitian people. I showed him the hospital which, seven days after the quake, still had no food or water for the patients (nor the doctors, nurses and staff). We still didn’t have stable power and were operating in dark rooms, the batteries of our flashlights dimming or dead. We still operate with hacksaws. Supplies are trickling in, but we have more doctors and staff now than supplies. This morning surgeons were operating without gowns or gloves. And without lights, again.

Later, one of the patients we operated on the first day — a woman with a beautiful smile, pony tail and an orange t-shirt — was septic and having seizures that wouldn’t stop. Maggots crawled out of the stump of her recently amputated leg. We (Partners in Health) are working to get the hospital up and functioning with food, water, supplies, power, sanitation, and security (we made significant progress after I emailed my contacts at the State Department — General Keen showed up after), but we have no communications internally and little organization. I ran over to the Norwegian team’s tent to find a bottle of seizure medication. They had finally set up after a week, getting their supplies and opening one mobile operating suit. The anesthesiologist gave me a bottle of phenobarbital. I looked down on the operating table and saw the surgeon cutting off a man’s leg above the knee. I realized it was Mitch, my friend from my first day, who now — seven days after the earthquake — was finally in the operating room.

My heart cracked and the tears came all day. Through the exhaustion, a of lack sleep and food, I had spent four days of getting to know these extraordinary people. Their spirit is indefatigable despite 200 years of natural and political disaster. With each story, the tears came: the young man asking for a job so he could bring food to his wife and children, who hadn’t eaten in a week; the well-known Haitian musician who, rather than escape a crumbing building, rushed up to the third floor to rescue a baby. He carried the baby in his arms, but lost most of his fingers as he protected the baby. George Boutin, my father-in-law, didn’t have the heart to remove his mangled fingers and hand. He reconstructed them so the musician could, perhaps, play music again. Maybe. Perhaps. Hopefully one day.

Today, the local hospital staff (nurses and workers) came back, at least those who were alive. They came even though their families were dead, even though they still slept on the street because their homes were in rubble, and even though most hadn’t eaten food for days. After 10 straight hours of operating in hot and dark rooms, the dark skinned nurses looked pale and weak. They worked without food or drink all day. In a back room of the main storage area I found a few cases of water meant for 5,000 people. I brought a few to the operating room to refuel the staff at 8 p.m. last night.

General Keen arrived to inspect the scene. The military are here to create life, support life, to save lives, to bring relief in a country where there is no local infrastructure. The NGO’s (non-governmental organizations) and United Nations struggle to get organized in the chaos. Their kindness and compassion made me cry again. They are organized and willing and focused. They are not here to provide security or make us safe, because there has not been one incidence of violence. There are only those gently, graciously asking for water or food or supplies or shelter from the sun.

This hospital was a disaster before the disaster. The Americans built the national public hospital in the 1930’s and there has been no support or funding from the Haitian government since then, except a small budget to pay salaries. I know we can raise the $30 million to rebuild the hospital, but wonder if it will be properly allocated because of the chaos in the government.

There is no remaining organization in Haiti to help us get the power back on or provide food and water for patients in the hospital. There is no one to get us medical supplies, or sanitation for the 4,000 people on the hospital compound, or get some of the overload of 1,000 surgical patients lifted to other sites. But General Keen’s 82nd airborne is organized, compassionate and capable of helping us build the National Hospital into what it was meant to be — the nation’s center for caring for the poor.

But today, when I got back to the hospital, all the patients that we had moved into the hospital’s remaining buildings were outside — strewn all over the hospital grounds. The aftershock shook them and frightened them. Those who had just had their legs cut off jumped on one foot out of the buildings. Others had their families drag them out for fear of getting caught in another collapsed building. The trauma is so deep and vast that even after we had the buildings cleared by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and announced it to all the patients, most were still to afraid to enter the buildings. As a result, many died from dehydration in the heat and sun. After five days of trying to rebuild the hospital, we had to start all over again.

But we did, and the people kept smiling back at me as I walked by.

Please donate to Partners in Health at http://www.pih.org. They are integrated with the Haitian health care system and can create a sustainable system from the ashes and sorrow.

Please share your thoughts by leaving a comment below.

To your good health,

Mark Hyman, MD

To see more of Dr. Hyman’s photos from Haiti go to:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/drhyman/sets/72157623158238557/

Beware: Some of the images are graphic.